“PHONETICALLY SPEAKING” To reflect the fast pace of world news, my blog is probably best served as a stream-of-consciousness text. Fast and unadulterated. With this approach, and on first encounter, text might not seem to scan. This is because I am dyslexic. Instead of keeping the proof-readers busy, I would rather let my blog updates of my visual work stand as a record of my experience of dyslexia, which I am keen that you now get to enjoy too. Unlike some news outlets, I hereby excuse myself the need for a ‘corrections’ section! The excitement of a new language is something I’m quite familiar with, and it is with this ‘joie de vivre’ that I am delighted to guide you through my thought and work processes, more phonetically (than fanatically) speaking.

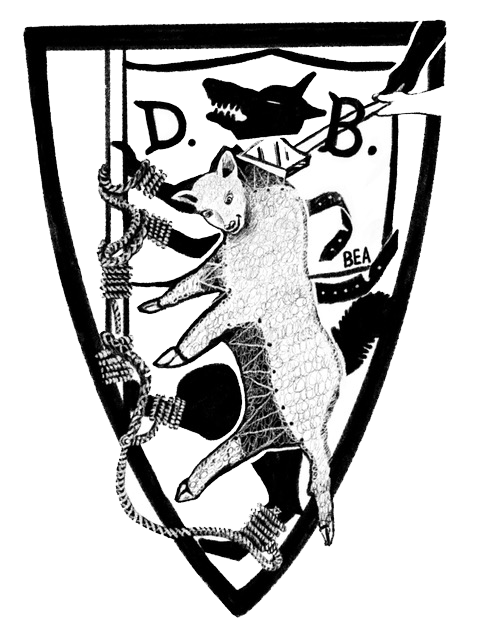

St George and the Day That Slipped the Nation

Philosophy in Motion: St George and the Day That Slipped the Nation

The English sent St George. That’s how the story goes. Not borrowed, not begged for sent. Not a saint of soft borders and shifting allegiances, but of iron will and sharpened lance. A symbol, not of empire or exclusion, but of resistance and moral clarity, wielding courage where confusion reigns.

So imagine the national chuckle when we found ourselves once again celebrating St George’s Day a week early. Why? Because Easter took precedence, and in these muddled modern times, we apparently can’t manage two things at once. True Englishmen knew. But our government didn’t.

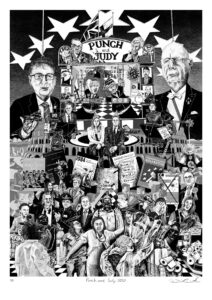

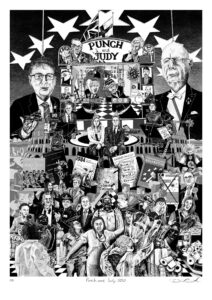

It’s comic, really. The Prime Minister, with all the gravitas of a game show host, stood up to congratulate Christians for Easter as though they were a separate group, an affiliate branch of the British project rather than its backbone. He said Easter helped “make Britain.” A baffling statement, considering that Christianity and Britain evolved together. To divorce one from the other is like separating the egg from the yolk and expecting a full English breakfast.

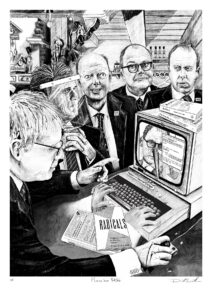

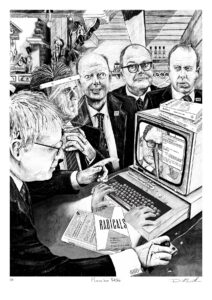

This is identity politics at its most tragicomic. The Christian tradition so deeply woven into British consciousness it’s practically in the rain now treated as an optional extra, like oat milk in tea. It’s not just ignorance; it’s low-IQ governance masquerading as inclusive brilliance. The sort that divides everyone up like school dinner trays and pretends that’s what progress looks like.

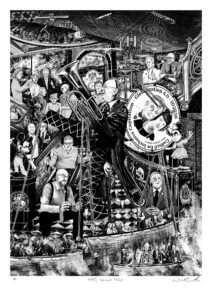

But where, I ask, was the Church of England in all this? Muted, neutered, lost in its own bureaucracy, seemingly incapable of whispering a reminder about the most basic of holy dates. They should have roared like the dragon George himself faced. Instead, they mumbled into a risk assessment form and hid behind a PowerPoint.

As for us? We’ll celebrate St George’s Day on the 28th. Because England real England doesn’t need permission to honour its heritage. We’ll do it late if we must, but never falsely. And let’s be honest: we’ve got dragons to slay. They’re not scaled and winged anymore. They’re bureaucratic, ideological, ill-informed.

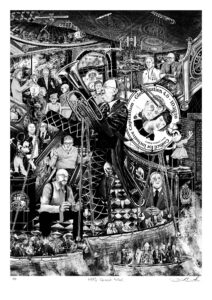

We need more myths, not fewer. More tales of Arthur, Gayne, and dragon-slayers those who stood up when the easy thing was to kneel. Myths teach us what our modern leaders cannot: courage, clarity, and a sense of nationhood that isn’t apologised for at every turn.

And here’s the truth: the English will win not because we are the strongest, not because we are the smartest but because we are the most stubborn. Tenacious in mind and spirit. We simply stand there longer than anyone else is willing to.

Even Napoleon, our old foe, came to understand this. He wrote,

“The British fight not because they love war, but because they will not surrender.”

And Hitler himself, during the Blitz, spat the words in frustration:

“The English are like a piece of chewing gum. The more you chew, the harder it gets.”

But perhaps the most fitting line comes from a weary German officer at Dunkirk, watching a nation evacuate in defiance rather than despair:

“You have to admire them. They do not know when they are beaten.”

And that, in the end, is the most English thing of all.